As investors, our goal is always to surface the true financial position of a company. In order to do that, we must have an accurate view of revenue and expenses. One of those expenses is depreciation.

How should we handle depreciation?

When it comes to investing there are two camps on depreciation. The first thinks it’s a non-cash charge that you can add back into your operating income to show more profit. The second, believes it is a real cost that effects your business. Here at WizeVest we’re all about breaking down the nitty-gritty to develop a better understanding of how to make sound investment decisions. Depreciation is one of those topics that usually gets swept under the rug and ignored. By the end of this article, you’ll know the truth about depreciation and how it should be factored in. Let’s look through some different ways to consider deprecation when you’re evaluating a company as a potential investment.

A great practice is to start with the end in mind. Our main goal in evaluating a business investment is to get to a per share value of the business. In order to do that, we need to be able to value the company as a whole and then translate that value into a per share number. Valuation is not an exact science, but getting to the most accurate figure possible is very important in investing. Before we can value the company as a whole, we must understand its cash flow. Before you can get to cash flow, you must determine earnings for the company. That’s where depreciation comes in. Depending upon how you consider depreciation, you can end up with very different levels of earnings. Thinking back to the opening lines of this article, I stated there were two camps on depreciation, that was in reference to its effect on earnings. One camp believes you don’t have to consider depreciation while determining earnings, the other regards its consideration as paramount.

Importance of Earnings

To understand depreciation, you must understand earnings and their purpose when it comes to investing. Another name for earnings is “net income.” A couple of things earnings represents are the output of the business and the amount of income that potentially can be distributed to shareholders. As investors we really care about what can be distributed to us, so the earnings of a company are a big deal. A particular company may not distribute all of its earnings, nevertheless, in theory, we have a right to that income. Without a clear perspective on earnings, we can’t have a representative estimate on value. Without that estimate our investment may be a poor move that deteriorates our net worth instead of growing it.

EBITDA and the Non-cash Depreciation Charge

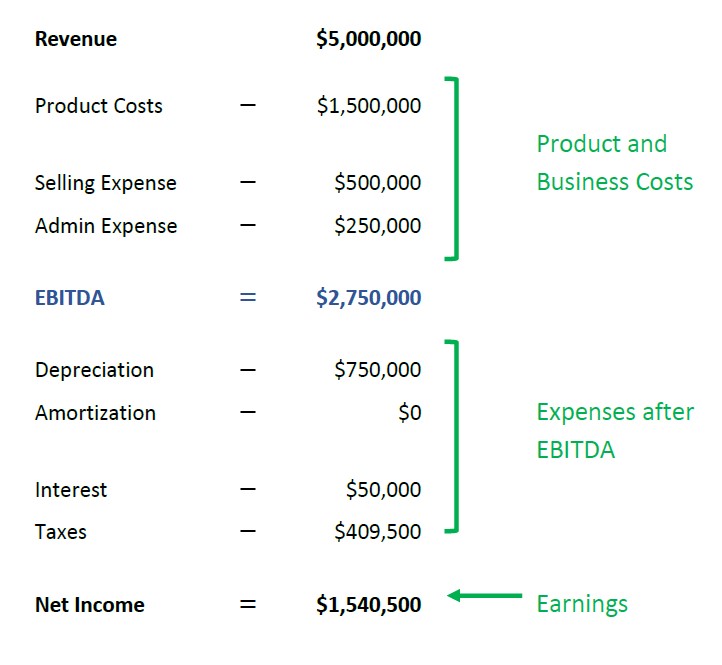

What exactly am I talking about here in terms of camp #1? How do people misuse depreciation? I’m talking about a very common substitute for earnings, EBITDA. The commonly used financial measure stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. The key word there is, before, meaning that earnings haven’t had depreciation removed. Since depreciation is not considered in EBITDA, the assumptions are that depreciation does not affect the value of the company, and EBITDA is a more accurate reflection of what the operations of the business can do.

When certain investors rely upon EBITDA, they primarily use it for two activities. First, they use it as a financial yardstick to compare other companies against, and second, they use it to determine the value of a company. The first use, as a comparison, isn’t as disastrous since every company is compared by the same yardstick. However, the reasoning behind using EBITDA as the comparing tool is misguided. It’s suggested that EBITDA is a better reflection of a business’s operations since it has “non-cash” charges removed. We’ll see why that is a faulty assumption later. The second use of EBITDA is for valuation purposes. That activity will likely lead to a poor valuation for whatever company you’re reviewing. Let’s follow the path from revenue to EBITDA to see why it creates such a flaw in valuation.

- First there is revenue.

- Then you subtract your business expenses such as product costs or selling costs.

- That brings you to EBITDA.

- In order to get to Net Income, you must then subtract Depreciation, Interest, and finally Taxes.

It’s easy to see that EBITDA will always be greater than net income since it hasn’t had something removed. When valuing a company using EBITDA, a “multiple,” will be used. You’ll take some ratio, usually compared to enterprise value (EV) and multiply it by EBITDA to determine a whole company value. EBITDA multiples can end up valuing a company higher than it’s true worth and may even end up showing a profitable company that, is in actuality, losing value over time. From the standpoint of the analyst using EBITDA, they think their valuation is best, because it’s easy, comparable, and “has had non-cash charges removed so it’s a more accurate reflection on the true output of the business.” We’ll see how that is an unwize way to think when valuing investments.

What is Depreciation really?

How exactly does depreciation fit into all of this, you might ask. Well, depreciation is either a non-cash charge that isn’t counted as a business expense, or is a real expense that affects profitability. In actuality it represents an expense that was already made by the company. A company will buy a large asset, like a special machine, that will cost a large amount in year one. This expense is called a capital expenditure and is made with after-earnings cash, so it doesn’t actually affect the income statement the year it’s purchased. Not affecting the income statement means it doesn’t affect earnings. Once the capital expense is made, there’s no cash payment in the following years. This further complicates the problem and a poor manager may lean towards not treating it as a real expense because it’s out of sight and out of mind. Without depreciation, it’s a silent charge on the business.

Comparing Depreciation to Inventory Expense

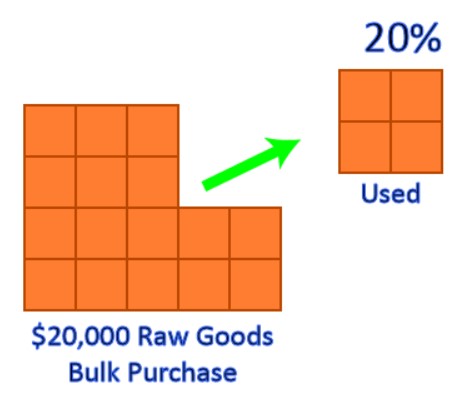

Not claiming the depreciation expense would be like not claiming an expense made on your raw materials used to make your product. Usually you buy those in bulk, one large purchase. But then you expense them as you sell your product. Wouldn’t it be crazy if you paid $20,000 for a bunch of raw materials and sold 20% of your finished goods in the second year but didn’t record the cost in the second year. All of a sudden, you’d be selling products that cost you nothing to buy. That doesn’t make sense! What makes more sense is when you tie your expense to the sale of the product. If you sold $4,000 worth of those raw materials, then you’d only expense the $4,000 and you’d do it at the same time you delivered the product. This means your expenses would match up to the time you fulfilled your contract with the customer, rather than when you bought the initial $20,000 bulk order of raw goods.

If it sounds crazy to handle your product inventory the way I just described, then why would handling a cost for another business asset be different, especially one as large as a typical depreciable asset. To illustrate the point, I’ll use that same example but with a depreciable asset.

An Example of Depreciation

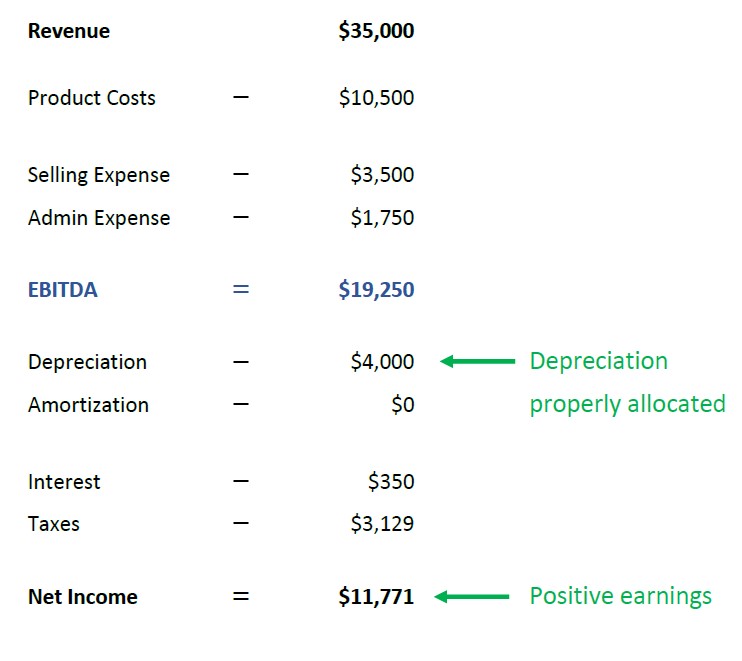

Imagine you bought a $20,000 truck for your delivery business. Under straight-line depreciation rules you’d apply $4,000 worth of depreciation expense each year, if that truck was to last 5 years.

You bought the truck in the beginning of 2023, so by the end of the year you should have applied $4,000 as an expense to your income statement, which would reduce earnings. Then in 2024 you should apply $4,000 again. Even though you bought the truck in 2023, you’ll need to apply the correct portion of expense in 2024. In the raw material example above, 20% of the goods were sold in the second year. If that was the case, then 20% of the $20,000 expense should have been applied in year two. In other words, $4,000 would have been applied to our income statement as cost of goods sold expense. Similarly, depreciation is an attempt to apply those costs to the period in which they benefit the company.

Depreciation is an attempt to apply those costs to the period in which they benefit the company.

In the example of 20% of the truck being used up in year 2, we’d apply $4,000 of the value of the truck to the income statement in year 2. The goal is to match the expense with the benefit. Even though a manager might not want to think about that large expense made in 2023 when it’s 2024, he needs to apply that expense to his business otherwise he might as well sell his goods while pretending he’s making 100% profit on them. The large capital expenditure he made on a truck or a machine is still a real cost and it really effects the profitability of the company.

These large capital expenses are spread out over the course of time since the assets, like the machine, are used over the course of time. A truck will last multiple years. A machine will last multiple years. A building may last as long as a decade. Since the first large capital expense doesn’t affect the income statement and thus earnings, you must eventually apply that expense to the business through future charges of depreciation. These charges will, over time, spread that large expense into smaller expenses that properly correlate with earned revenue of future periods. Without application of depreciation, the asset cost, won’t even be accounted for within the business operations. It will affect the net worth (balance sheet) of the business since it will reduce cash, but it won’t affect the operations. In other words, it’ll be like you’re operating with free assets. Any business using a free asset will look very profitable.

Without application of depreciation, the asset cost, won’t even be accounted for within the business operations.

Factoring in Depreciation all Upfront

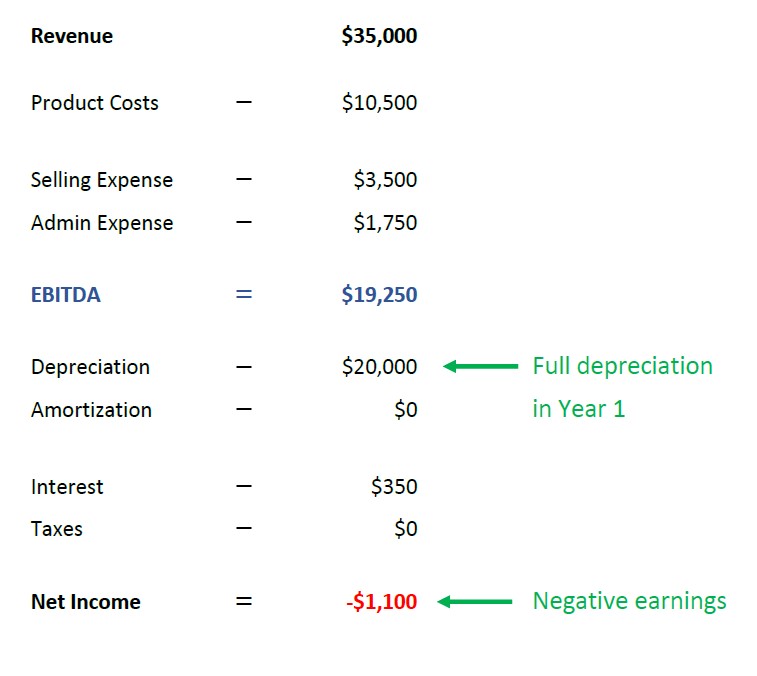

By looking at it one other way we can see how depreciation will offset profits. If we decided not to spread the expense of the asset over multiple periods and instead lump all of that expense into one period, we can also dramatically affect business operations.

We’ll use the same example we’ve been working with. The managers of the business bought a $20,000 truck. In the hypothetical example, instead of spreading out that expense, they applied it all to the year they bought it, 2023. What happens to profitability that year? It is significantly decreased! That one expense could wipe out the entire profit for the year. Larger businesses would make much larger capital expenses which in turn would affect profit for those businesses in the same way. Let’s compare two income statements, one with depreciation lumped into Year 1 and the other with it properly applied.

Full depreciation in Year 1

Proper depreciation application

What about the next year? In 2024, there would be no need to buy a truck since the business already owned one. What would profit look like in 2024? It would be substantially increased. Since the business had no large expense for the truck and no partial expense for a previously purchased truck, it would have much higher profits. To fully understand this effect, imagine the capital expenses at a very large scale, and imagine a company making multiple capital expenses in one period. Quickly the large expenses increase, so profit would drop sharply if these were all expensed at once. Therefore the need for proper application to profits in a particular period is critical. In fact, accounting rules force managers to spread out the capital expense through depreciation. Poor investment analysts will choose to ignore this charge which is similar foolishness as expensing the total charge in the year it was made.

In Summary

Since our mission as investors is to uncover a true picture of the profitability of a business, we need to account for all expenses, even the ones that have happened in the past. As you might conclude, I’m definitely a member of camp #2. I believe depreciation is a real cost that effects a business’s operations, and thus its overall value. When evaluating company profitability, as wize investors, we should apply depreciation expense to reach a real earnings number.

Jeff G. | MBA

Jeff G. | MBA